No, Newton’s cradle was not even on my list of candidates, nor any of the other toys on Michael Scott’s desk in NBC’s The Office. I don’t play with tin toy robots either, though I have a collection of miniature industrial robots. If you design serial or parallel robots, or if you simply love 3D geometry, then the following three desk toys are a must for your office (as is a 3D printer). Here are some exclusive background facts regarding my most favourite office toys, as well as some examples of how these educational toys can inspire engineers.

No, Newton’s cradle was not even on my list of candidates, nor any of the other toys on Michael Scott’s desk in NBC’s The Office. I don’t play with tin toy robots either, though I have a collection of miniature industrial robots. If you design serial or parallel robots, or if you simply love 3D geometry, then the following three desk toys are a must for your office (as is a 3D printer). Here are some exclusive background facts regarding my most favourite office toys, as well as some examples of how these educational toys can inspire engineers.

Roger’s Connection®

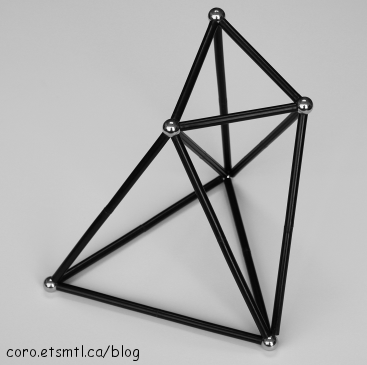

My very first office toy (before I even had an office) was the popular balls-and-magnetic-rods building set called Roger’s Connection®. It consists of steel balls and sturdy plastic rods with recessed neodymium magnets at the extremities.

In 1989, Roger Silber, an electrical engineer based in Iowa, then in his thirties, came up with this brilliant idea while exploring advanced alternative energy systems. It took several years before Mr. Silber decided to pursue his invention commercially. In 1995, his toy won the prestigious Parents’ Choice Award (Silver Honor) as well as the Oppenheim Toy Portfolio Gold Seal Award, and in 1996 he set up his web site and started selling it directly. He later presented his product on the popular QVC shopping network and it became the longest selling toy on QVC.

Roger’s Connection® is one of the best educational toys. Many other companies build copies of that toy (Geomag®, Magnetix®, Supermag®, etc.), but all of these copies feature much shorter rods.

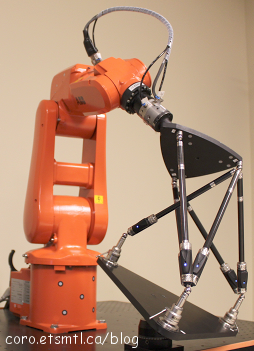

It was while brainstorming with my old Roger’s Connection® set that I came up with an innovative method for measuring a set of poses with a single Renishaw telescoping ballbar. The idea is that given a triangular base, a triangular end-effector and six “legs” of equal length, there are 72 different “hexapods” with trivial direct kinematics that can be built. Hence, there are 72 poses that can be measured by measuring the “lengths” of these virtual legs with the Renishaw telescoping ballbar.

Probably the best examples of the usefulness of Roger’s connection to engineering are the Tetronom® and Octonom® metrology artifacts by German firm AfM Technology. The latter are basically a tetrahedron and an octahedron, respectively, made of precision balls and calibrated bars with magnetic ends, and are used for inspecting Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs) and machine tools. Similar artifacts are manufactured by INORA Technologies, of USA.

Rare-earth magnetic balls

Magnets are fascinating, but rare-earth magnets are even more so. I purchase mine from K&J Magnetics and use the small cylindrical ones to build custom magnetic nests for the spherically-mounted reflectors (SMRs) for my FARO laser tracker or to build magnetic tooling balls for robot calibration.

Surely, the coolest shape for magnets is the sphere. I can’t believe that it was as late as in 2009 that a number of US companies finally started to repackage ball magnets and sell them as educational toys. The most successful of these companies was Maxfield & Oberton, New York City based maker of the notorious Buckyballs®. I got my set of magnetic spheres from Zen Magnets though, a much smaller firm from Colorado allegedly manufacturing more precise balls. Unfortunately, neodymium magnets are extremely dangerous if swallowed, and these desk toys were eventually banned in several countries, including the USA and Canada, despite highly mediatized protests. By the time Maxfield & Oberton ceased to exist on December 27, 2012, more than three million sets of Buckyballs® and Buckycubes® had been sold in the USA alone.

Given sufficiently many magnetic balls, you can build any imaginable sculpture. I should admit, however, that the most complex structure that I have built is a pyramid, which only gave me a crave for some Ferrero Rocher®.

The Klixx fidget toy

Two weeks ago, I bought a set of Twiddle, a chainable clickable building block toy, while vacationing in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The toy, which consists of a series of identical connectable links, was released last June. It is sold by Zorbitz, a multi-million dollar US company selling… bracelets and necklaces. Although Zorbitz has recently filed a provisional patent application (# 61/769,710), the toy is actually a modified copy of Klixx.

Klixx was invented and patented by Ronald Milner and Eric Plambeck of ADL, California, in 1991. Both are engineering graduates from the University of California, Berkeley. Tom Walker, a friend of Mr. Milner, built a small company, Chase Toys, to sell it. According to Mr. Milner, the toy was very popular for a couple years but “ran out of steam after never being able to get into the big retailers.” Eventually, the patent was sold to Chase Toys in 1995, which in 1999 granted the rights for manufacturing and distributing the Klixx to POOF Products, the manufacturer of the famous Slinky®.

Klixx no longer exists, but a near exact copy of it is sold by Toysmith, under the name Wacky Tracks. While Wacky Tracks (sold for only $4, versus $10 for Twiddle) comes in cheap packaging and is less refined than Twiddle, it is way better for construction purposes. Indeed, while the joints of Wacky Tracks snap firmly at ±90°, ±45° and 0° with a pleasing clicking sound, the joints of Twiddle snap flimsily at only ±90°. In fact, Twiddle is basically a necklace. It even comes with necklace clasps.

Of course, no one can miss the similarity between the Klixx fidget toy and the popular concept for modular robots. The most recent such robot is the Linkbot, soon to be manufactured by Barobo, a spinoff from the University of California, Davis.

All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy

Next time you see construction toys on the desks of your employees or graduate students, think twice before you scold them. Unfortunately, my graduate students have only coffee machines and kettles on their desks. Don’t they know that caffeine can cramp creativity.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts